12 Angry Men

The defense and the prosecution have rested and the jury is filing into the jury room to decide if a young Spanish-American is guilty or innocent of murdering his father. What begins as an open and shut case soon becomes a mini-drama of each of the jurors’ prejudices and preconceptions about the trial, the accused, and each other.

IDOLSPOILER.COM Review

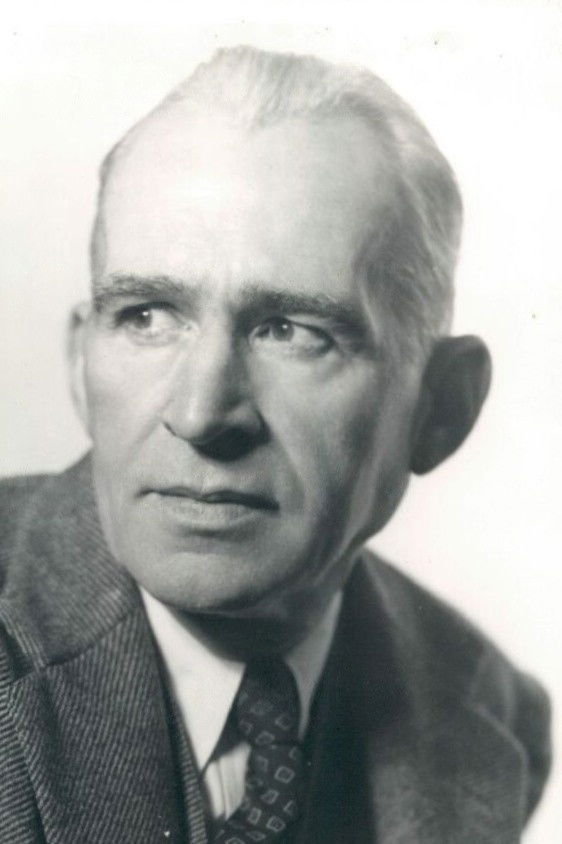

Sidney Lumet’s 1957 masterpiece, *12 Angry Men*, is not merely a film; it is a surgical examination of justice, prejudice, and the fragile edifice of human reason. Confined almost entirely to a single, sweltering jury room, Lumet orchestrates a masterclass in tension and character development, proving that the most profound dramas often unfold in the most mundane of settings. The film’s genius lies in its audacious simplicity: a dozen men, a life on the line, and the slow, agonizing unraveling of preconceived notions.

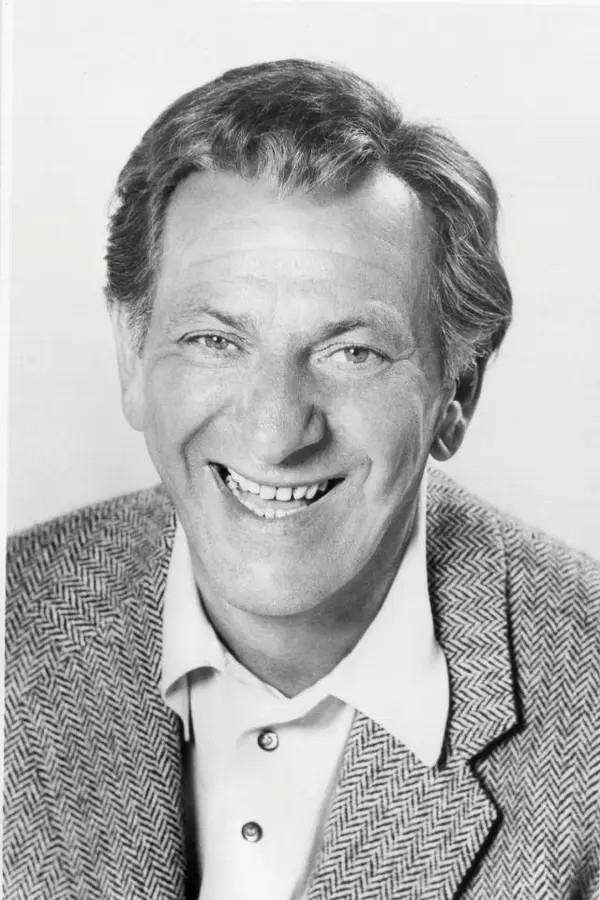

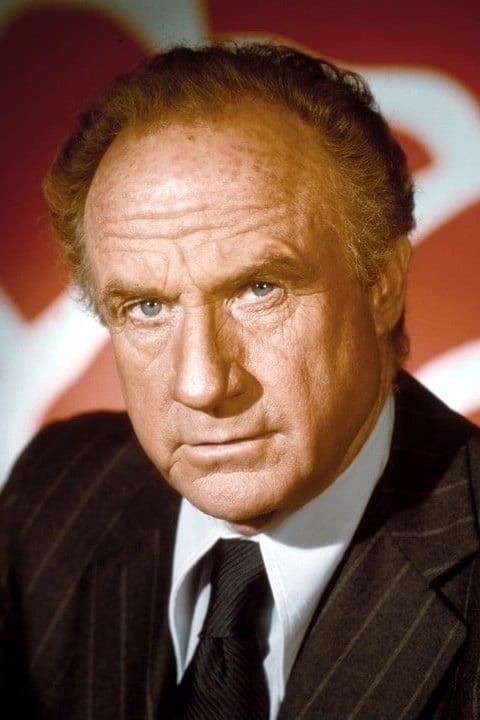

The screenplay, a marvel of tightly wound dialogue, transforms what could have been a static procedural into a dynamic psychological battleground. Each juror, initially a caricature of a societal type, is meticulously peeled back, revealing layers of resentment, insecurity, and, occasionally, empathy. Lee J. Cobb’s Juror 3 seethes with a personal bitterness that warps his judgment, a performance of raw, almost terrifying intensity. Conversely, Henry Fonda’s Juror 8, the lone dissenter, embodies a quiet, unwavering moral compass, his conviction born not of certainty, but of a profound respect for due process. His performance is less about grandstanding and more about the subtle power of persistent, rational inquiry.

Lumet’s direction is nothing short of brilliant. The claustrophobic cinematography, with its gradually tightening camera angles, mirrors the escalating pressure within the room. As the film progresses, the lens seems to close in on the faces, amplifying every bead of sweat, every flicker of doubt. This isn't just visual flair; it's a deliberate artistic choice that immerses the viewer in the suffocating atmosphere of the deliberation. However, while the film excels in its exploration of prejudice, its resolution, while satisfying, occasionally flirts with a slightly idealized vision of justice prevailing. The transformation of some jurors, though earned through compelling argumentation, feels almost too complete, a touch too neat for the messy reality of human nature.

Despite this minor quibble, *12 Angry Men* remains a timeless testament to cinema’s power to dissect societal flaws. It challenges us to look beyond the obvious, to question our own biases, and to understand that true justice is not a given, but a hard-won victory of deliberation and intellectual courage. It is a film that demands to be seen and, more importantly, to be felt.